|

As much as we love swashbuckling adventure and daring sword

fights in our books and movies about the 18th century, everyone knows that the

widespread use of gunpowder weapons made swords and other hand-to-hand weapons archaically

obsolete by the time of the American Revolution, right? Well, maybe not. In

this edition of Mansion Mythbusters we take a look at the fascinating, and

under-served, subject of martial arts in 18th century North America.

The Breakdown: While the battlefield was certainly dominated

by firearms, hand-to-hand combat was still a very real part of 18th century

warfare. Beyond that, however, the North American colonies were home to a

vibrant array of martial arts at every level of society. Many of these were

carried over from Europe, while others were indigenous to North America. Still

others developed as a hybridization of European and American martial

traditions.

To break this down, framing the terminology will be

important, especially given the many misconceptions about what martial arts

are, and what martial arts are not. For example, martial arts are not exclusive

to Eastern Asia. While Eastern Asia is home to numerous ancient and modern

martial arts traditions, the term martial arts applies to any tradition or

method of close-quarters combat which prepares the practitioner to enact and/or

resist violence in earnest. Martial arts traditions have existed all around the

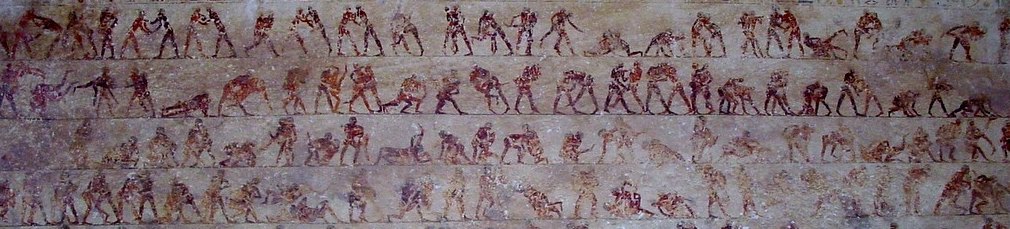

world from the earliest points of human history (some of the earliest

depictions of martial arts training date back to ancient Egypt). For colonists in 18th century North America, European martial traditions offered a

fertile ground for the continued practice of the Arts of Mars.

|

| Wrestling holds from the tombs at Beni Hasan in Egypt, one of the oldest extant depictions of martial arts in existence. |

A complete overview of North American martial arts is well

beyond the scope of this article. Instead, we’ll focus on a handful of examples

intended to illustrate the diversity of martial arts present in colonial

society and the degree to which they were a present part of daily life for many.

We’ll start by looking at hand-to-hand combat in the military.

For European armies of the early 18th century, hand-to-hand combat with sword

and bayonet was not uncommon, whether storming an enemy fortification or in the

grinding, constant garrison duty which filled the majority of a soldier’s life.

One of the most famous swordsman of the British army was a Scottish fencing

master named Donald McBane, whose military career included side occupation as

an instructor of swordsmanship, duelist and prize-fighter, and brothel-owner.

North American service had a number of major differences from service in Europe,

however. By mid-century, British officers in North America determined that the

common soldier had no need of his issued hanger (a short infantry sword,

sometimes referred to as a cutlass) when serving in the rough wilderness where

mobility and light loads were key to survival and military success. This is

often taken to mean that the troops had no need for a sword in general, however

many units did continue to be issued hangers while performing garrison duty

through the end of the Revolutionary war.

|

| A View of the Church of Notre Dame de la Victoire, Québec, 1759. While North American soldiers often left their swords behind when going into the field, those in garrison generally kept them close at hand, as depicted here. |

During the buildup to revolution, British troops clashed

with angry mobs in the cities of the colonies. Descriptions of these conflicts

often mention British troops using their swords to good effect. A highly

sensationalized propaganda account of “The Battle of Golden Hill”, which took place

on January 19th, 1770 in New York City, describes separatist citizens and

British soldiers fighting in the streets armed with sleigh rungs and swords.

The sword was also not the only side-arm of the enlisted man.

British and American soldiers were issued a bayonet as part of their stand of

arms. This side-arm remained in use even when swords became less common, as it

could be fixed on the end of the musket to form a spear-like weapon, held by

the socket for employment as a short thrusting sword, or held in a reverse grip

by the blade itself (as it was primarily a thrusting weapon, the edges of the

spike-bayonet were un-sharpened) for use as a dagger or to apply leverage in

grappling in the same manner as a Scottish dirk. On the battlefield itself, the

threat of the bayonet charge could be as effective as the physical application

of the steel itself, allowing units to gain ground which, once gained, was held

through concentrated application of musket fire.

The British were not the only ones who recognized the

importance of the bayonet. Washington and other American leaders issued or recommended spears as a substitute for the bayonet when the genuine article was

unobtainable. This was especially important in siege warfare, when employing defensive

field fortifications, or for defense against cavalry (who were ever poised to

ride down disorganized bands of infantry).

These martial traditions were not reserved to the military world

by any means. The most familiar form of 18th century martial arts for many

people is fencing with the smallsword. The smallsword had a slim blade designed

for fine motion and deadly thrusts, even against an opponent clad in the heavy

wool and linen clothing of the time. The earliest fencing treatise in North

America was by Edward Blackwell, and was published in Williamsburg, Virginia,

by a Mr. William Parks. While instructors of swordsmanship were not as common

in the colonies as they were in Europe, the cities of the East coast attracted

a decent number of masters and would-be-masters, often doing double duty as

dance instructors. Still, the most aspiring young swordsmen, including

Alexander Hamilton’s friend John Laurens, traveled to Europe to hone their

skills.

|

| Images from Sir William Hope's New Method of Fencing, depicting the smallsword in practical use against other swordsmen, in the grapple, on horseback, and even against much heavier weapons such as the Lochaber axe. |

Martial skills were not only taught in the refined schools

of the colonial cities however. Folk martial arts flourished as well, with

traditional wrestling and grappling skills forming part of the upbringing of

almost every working-class man. More lethal weaponry found its way into the

hands of the citizenry as well. For instance, while the “Boston Massacre” is

popularly depicted as a merciless slaughter of unarmed civilians by leering

British soldiers, eye-witness testimony and the deposition of actual

participants tells a very different story of a crowd armed with clubs, rocks,

and even swords. According to Benjamin Burdick, a participant in the riot:

I had in my hand a highland broad Sword which I brought from home. Upon my coming out I was told it was a wrangle between the Soldiers and people, upon that I went back and got my Sword.

I never used to go out with a weapon. I had not my Sword drawn till after the Soldier pushed his Bayonet at me. I should have cut his head off if he had stepd out of his Rank to attack me again.

|

A mid-18th century highland broadsword similar to the type carried

by Benjamin Burdick at "The Boston Massacre". |

What of the Schuylers? The men of the family, or at least

the sons-in-law, are famous for their dueling (both John Barker Church and

Alexander Hamilton met with Aaron Burr for duels, with rather different

results). Even Philip himself was involved in a duel in May of 1769 while a

member of the Provincial Assembly, though the situation was resolved without

the loss of life. These duels, however, were all conducted with pistols.

However, on February 27th, 1769, Henry Van Schaak of Albany wrote to his

brother to describe a fascinating incident involving Philip Schuyler:

The dispute between Col. Schuyler and the brewer Anthony… was briefly this: the latter had said, at the Coffee House, that the aim of the Colonel’s motions in the House was popularity, and added something which I forget. The colonel immediately armed himself with his sword, went to the Coffee House and other public places thus arrayed. I saw him come in this manner into the house of Assembly, ‘tis said in search of Anthony, not meeting with him, he called upon his at his own house where he says he asked his pardon.

Beneath the reserved tone of the letter, what we have here

is a description of Philip Schuyler as a man ready and willing to settle

slights of honor at sword point (and pistol point that same year). While there

is no clear information about Philip’s level of training as a swordsman, his

service in the British army would have afforded him the opportunity to achieve

a basic appreciation of the handling of such a weapon. While his actions were

primarily those of a scorned aristocrat, it appears that 18th century society

was martially competent enough to make it unlikely that his threat was an

entirely empty one.

We're back with new articles every week as we roll into 2017. There's lots to explore so stay tuned! Have you heard stories about the 18th century or the Schuyler family that make you scratch your head? Know any longstanding myths that you'd like us to take a crack at? Let us know in the comments or on our Facebook page, and your suggestion just might be featured on an upcoming Mansion Mythbusters!

Want to learn more about fencing (specifically as the term applies to swordsmanship) in Colonial America? click here!

*See page 41 for one of the best descriptions of such an affray.

No comments:

Post a Comment