"The King Drinks a Twelfth Night Feast," about 1645,

by Jacob Jordaens.

by Sarah Lindecke

Twelfth Night of January 1775 likely looked different from past Twelfth Nights for the Schuylers. The political tension was unavoidable as American colonists faced numerous acts, foisted upon them by the English Parliament, restricting their purchasing of imported consumer goods, like sugar and tea. Combined with many colonists feeling over-taxed and over-burdened, many were pushed toward the idea of separating from England, though the sentiment was not universal. On top of these already tenuous conditions, goods and food normally used at the Schuylers’ lavish holiday celebrations had recently come under direct attack, too, but not by the British—by the colonists boycotting British import and export trade. Suddenly, the sugar, rum, Maderia, fancy silks for clothes, and even exotic fruits such as oranges, lemons, and pineapples, were off-limits… Unless the Schuylers crossed the boycott lines

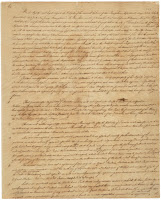

|

| Page 1 of the Articles of Association |

The boycott came into effect through the Articles of Association, or the Continental Association, which was passed by the Continental Congress on October 20th, 1774, and went into effect on December 1st, 1774—just over a month before Twelfth Night. This set of Articles bound the colonies in unity under a non-importation/exportation agreement that banished all goods from or traded by England until the colonists’ demands for fairer treatment were met. The colonies wanted to significantly damage the financial strength England wielded over them through their import/export trade. The Association was also meant to promote the home-grown industry of the colonies to produce goods for local use. Local committees, known as Committees of Correspondence, were charged with enforcing the non-importation/exportation elements of the Articles while ensuring people were able to access necessities.

Despite the unification felt by many colonists under the Articles, some

of the wealthiest members of colonial society chose to forgo compliance with

the Articles for their own comfort. Philip Schuyler [and his family were among those able to pick and choose how they wanted

to comply or not comply with the new law. Though the family eventually became

deeply involved with the rebels once the American Revolution began later in

1775, they were more interested in their own comfort and lavish lifestyle

before joining the rebels. Many of the items they purchased

for decoration, as well as for consumption, were imported. It was a status

symbol to purchase a majority of goods from far flung lands, and the Schuylers

were always concerned with status. They were personally and socially pressured to show off their wealth

through the imports in their home and on their table.

Unfortunately, access to imported

merchant goods became complicated after the Articles of Association went into

effect. The Schuylers were at a crossroads—adhere to the Articles and risk appearing common or

find other ways to continue purchasing imported goods. A letter addressed to

Philip Schuyler on January 1st, 1775, from Ludlow Shaw & Ludlow,

a trading company in New York City, hints at what lengths the Schuylers were willing

to go to acquired now-blockaded goods. Ludlow wrote:

We hope the

different parcells [sic] of goods we have Sent you up are got to hand _ and

that they are aggregable to order _ the 10 hails we have a promise of

which must remain here till the Spring, from the appearance of things we have

no Expectation of any importation from great Brittain for a

long timeIn a lengthy

postscript, the Ludlow Shaw & Ludlow company further elucidates the

relationship the Schuylers were building with them:

It is Customary

with us from to time to time to give our Country Friends every Information we

can respecting the price of prospect of Markets. For Grain for the

Insuing [sic] Spring; our only fear s are that Government may put a stop to our

Exports. Should that be cas [sic] great must be our distress_ but should not

that take place … we think wheat will… be in good demand next Spring from the

different advicses [sic] we have received _ But… we think in some measure to

repay the Risk the purchases of Wheat Run they should take its in low _ Pott ash

perhaps may be thought an object worthy your attention

|

| "Vue de la Nouvelle Yorck" by Balthasar Friedrich Leizelt |

The postscript

calls the Schuylers “Country Friends” of the company, or people who lived far

from the centers of importing and exporting, but who wanted to continue receiving

trade goods. In exchange, these “Country Friends” provided farm exports that were

desired by people living in cities. The postscript suggests that the Schuylers

have contracted to provide grains to the company as part of their payment. This

would have been a desired crop because New York City, while connected to many

farms up north of the city itself, required more food crops from much further

north to ensure all were furnished with regular goods. The writer is desirous

of receiving those goods, but wants to keep Schuyler informed that both the

company and the Schuylers were placing themselves in danger should the illegal

exports be found out. The government, the Continental Congress, had the power

to put a stop to all of their activities. While appearing cognizant of the

dangers, the company used the postscript to assure Schuyler that all cautions were

being taken for the financial benefit of all involved.

|

| "The Bostonian Paying the Excise-Man," 1774. |

The legal trouble

for both the company and the Schuylers as they conducted

these black-market deals came from the Committees of Correspondence that were established

locally and sanctioned by the Continental Congress in the Articles of

Association. These committees’ primary role was in disseminating information

and rulings made by the Continental Congress in support of the “Patriot”

movement. Due to loose regulations, many of these committees expanded their

role into the realm of enforcing Congressional decisions and rooting out

Loyalists agents. Philip Schuyler, later on in the Revolution, worked with

these Committees when he created lists of Albany Loyalists, but, prior to the

Revolution—and even during it—he was breaking

the laws enforced by the Committees.

While Schuyler’s wealth likely protected him from a majority of the possible censure, the social risk of having his loyalties questioned was present. If Schuyler was caught breaking any Continental Congress rulings, he could have been censured or steeply punished by the Committees and their agents. In New York, the Committees mainly resorted to social and political censure, but other colonies where more radical groups, like the Sons of Liberty, were in charge of the retaliation, often responded with more unrestrained violence. Images of extreme violence done towards citizens stem from more radical or violent responses to non-compliance to the Continental Congress’ propositions, but were somewhat rare on the whole throughout most colonies. These concerns were not enough, however, to force the Schuylers to go without their desired goods.

This letter is one

clear example of Philip Schuyler’s actions with the black market during the

pre-Revolution years, but there are more. Another example is in a letter written

to Philip Schuyler by friend and business partner, John Taylor, who purchased

goods for Schuyler during the Quebec Campaign during March of 1776 (If you are

interested in learning more about this, please check out our blog post Taken Up North Sold

For A Carpet). The items purchased in 1776 were similarly

precarious for Philip Schuyler due to the trade embargos in place at the time.

.jpg) |

"Still Life With Fruit and a Cockatoo" |

Bibliography

Breen, T.H. The marketplace of revolution: How consumer

politics shaped American independence (Oxford University Press, 2004)

Ketchum, Richard M. (2002). Divided Loyalties, How the American Revolution came to New

York. Henry Holt and Co.

Levy, Barry. (2011). tar and feathers

and English identity.

Norton, Mary Beth. 1774: The Long

Year of Revolution (Vintage, 2021).

Oliver, Peter. Origin &

progress of the American Rebellion; a Tory view (1961).

Schlesinger, Arthur Meier. The Colonial Merchants and

the American Revolution, 1763–1776 (1917).

Warford-Johnston, Benjamin. “American Colonial Committees of Correspondence: Encountering Oppression, Exploring Unity, and Exchanging Visions of the Future.” The History Teacher 50, no. 1 (2016): 83–128. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44504455.