by Ian Mumpton

One of our ongoing projects at Schuyler Mansion is to

attempting to uncover the identities, relationships, and, where possible, the daily

lives of more than thirty people of African descent enslaved by the Schuyler

family. Two of our recent articles have focused on specific individuals or

groups of individuals mentioned in the surviving documentary evidence (to read them, click here or here). Both of

these articles have been about men, however the Schuylers lived off of the

labor of both men and women. It can be difficult to determine exact figures,

however later records suggest a near equal divide between male and female in

the enslaved population of the household. For example, in 1798, Philip Schuyler

was listed as owning eleven slaves, including three men and one boy, and three

women and two girls. Similarly, the manumission record filed after Philip’s

death in 1804 established the free-status of two men, two women, and three

children (two boys and one girl).

|

| A modern recreation of a light laundry day. The enslaved women of Schuyler mansion would have dealt with much more clothing than this for a household as large as the Schuylers. |

Clearly, the labor performed by enslaved women was

considered valuable enough for women to make up roughly 50% of the enslaved

workforce of the family. Despite this, women are mentioned far less frequently in

the surviving documentation than men. For example, a receipt from 1771 for shoe

purchases and repairs mentions twenty enslaved people by name. Fifteen of those

listed (75%) are men, while only five (25%) are women. This doesn’t necessarily

indicate a larger male population than female; simply that in the Fall and

Winter of 1771 more men needed new or repaired shoes than did women. This can

give us an indication of the differences between the work performed by enslaved

women and enslaved men. As mentioned in previous articles, many of the men were

tasked with transporting goods and people between Schuyler’s properties in

Albany and Saratoga. Others appear to have assisted with mill work and were put

to work cutting timber. This sort of labor would have worn out shoes more

quickly than the primarily indoor, domestic work performed by women. That is

not to say that this work was necessarily more arduous than the hours of

hauling water (at least 260 lbs. of water were needed for a laundry day),

scrubbing clothing and dishes, and other chores tended to by enslaved women;

the nature of the work simply required more travel time, thereby causing men to

appear more frequently in the receipt.

One of the difficulties in reconstructing specific details

about the lives of enslaved women in the Schuyler household arises from the

fact that, unlike their male counterparts, women are very rarely referred to by

name in the surviving documents. Of the thirty eight named individuals clearly identifiable

in the documents as enslaved, twenty-nine (76%) of those identified by name are

men or boys. Nine (fewer than 25%) are women or girls: Bet, Britt, Diana, Jane,

Libey, Moll, Phoebe, Silvia, and Tallyho. Instead, Philip's letters and business

papers refer to women in general terms, even in sources where men are referred

to by name. For example, according to a medical receipt from 1755, Philip

paid for medicine for two enslaved people. The man is identified as Mink, while

the woman is only identified as “your Negro woman”. In 1762, the Schuyler

family paid for the field labor of “a Negro man and Wench”, neither of whom are

named in the source. In 1788 John Bradstreet Schuyler received a letter from

his father, Philip, discussing his recent purchase of “a wench” from a man

named Wendell for £60.

Explaining this disparity is difficult, but there are

several possibilities. The documents which preserve this information were

written by Philip Schuyler, his sons, and their male business counterparts.

Most of them are letters describing travel or transportation of goods between

Albany and Saratoga. They are almost entirely devoid of discussion of domestic

tasks and daily life in the home, which would have been largely administrated

by Catharine herself. Unfortunately, only one of Catharine Schuyler’s letters has survived,

and it makes no reference to the enslaved servants. This lack of documentation

results in a historical silence regarding the labor of enslaved women - one

which is very hard to break.

One example from family sources which indicates the differing spheres of male and female supervision of slaves comes from Johannes Van Rensselaer’s (the father of Catharine Van Rensselaer Schuyler) 1782 will which stipulated that his wife was to receive “one negro wench” and “a negro boy called Rob” upon his death. In this case the woman is unspecified because Mrs. Van Rensselaer was expected to choose who she wants to keep, however John specifies that she also keep Rob. Rob is described as a coachman, and his labor would have fallen under John’s supervision.

|

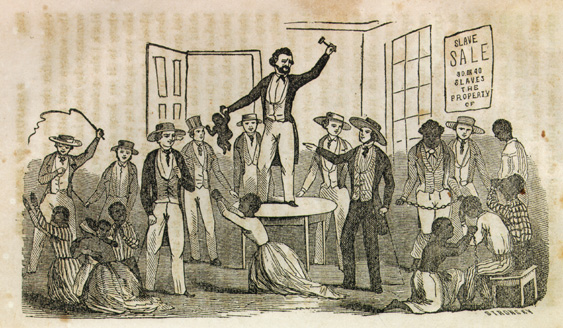

| A 19th century Abolitionist print depicting the breaking of a family, as an infant is sold away from their mother. While intended to arouse sympathy for the enslaved, the raw emotion of the print captures the reality of too many individuals who found themselves separated from their loved ones. |

More often it is possible to perceive enslaved women in

terms of their relationships with other people. For instance, Philip mentions to

one of his children in a letter from 1782 that, “Your mama will strive with all

in her power to procure you a good wench[.] They are rare to be met with, the two

which I bought Last fall out of Charity, least [sic] their master… should

dispose of them contrary to their inclinations, prove worthless in the extreams

[sic].” While neither woman is mentioned by name, this tells us several things.

First, that these two women had some sort of close relationship, be that mother

and daughter, sisters, or simply close friends. Second, we know that this

relationship was strong enough for them to indicate to Philip their desire not

to be separated. Separation from loved ones was a common situation for enslaved

New Yorkers, as the number of slaves owned by any one family was relatively

small, “necessitating” the sale of family members away from each other.*

While the daily lives of the women enslaved by the Schuyler

family may be hidden by scarce historical resources, even more so than for

their male counterparts, by combining close readings of the existing sources

with demographic records and a contextual understanding of the wider

experiences of enslaved women, we hope to begin to uncover more information

about their experiences in some of our upcoming articles. Stay tuned! In the

meantime, make sure to check out other series on the restoration of the mansion, explore the fascinating face of the Revolutionary War in the Northern Department, explore our collections and documentary evidence, and challenge some longstanding myths with Mansion Mythbusters.

What sorts of questions do you have about the lives of “the Servants”? Let us

know in the comments!

For an examination of the amount of labor that went into tasks like laundry, click here to read an excellent interpretive piece from Woodville Plantation in Pennsylvania.

* To what degree Philip attempted to avoid this or not will

be the topic of an upcoming article.

No comments:

Post a Comment